Blacklisting Colin Kaepernick? (Some) Evidence from NFL Contracts

August 2017

Former 49ers quaterback Colin Kaepernick almost won the Super Bowl in his first professional season. A promising career beckoned. Then, last year, he took a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality. Pledging to donate $1M of his salary to activism (so far he has donated 70%), Kaepernick explained his protest to the press in August 2016: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.”

Kaepernick’s popularity vanished overnight. Some fans burned his jersey. A national debate about peaceful protests and honoring America ensued. It even crept into the presidential race: Donald Trump claimed team owners were afraid to hire Kaepernick lest Trump incite his base against them.1

Kaepernick opted out of his contract with San Francisco after the 2016-2017 season to enter free agency, and feeling he had made his point, he announced he would end his protest. Still, no team will hire him. Some think he will never play again.

Despite appearances, Kaepernick is a not a pariah. While only a handful of peers joined his protest, he is still regarded as a highly-capable quarterback. FiveThirtyEight showed that quarterbacks of his caliber are almost never without a job this late into free agency. So far he has spoken to three teams: the Seattle Seahawks, the Baltimore Ravens and the Miami Dolphins. Seattle and Miami passed.

Baltimore were on the fence. A recent exchange between a fan and Steve Bisciotti, owner of the Baltimore Ravens was telling. The fan asked whether hiring Kaepernick would hurt the Raven’s “brand”. “Quantify hurting the brand,” he responded:

“I know that we’re going to upset some people, and I know that we’re going to make people happy that we stood up for somebody that has the right to do what he did.”

He wasn’t kidding:

Baltimore eventually declined to sign Kaepernick.2

Some believe teams are coordinating against Kaepernick. The same unnamed general manager estimates the number of teams unwilling to sign Kaepernick for purely sporting reasons or compensation demands at twenty percent. If true it would be remarkable. Why would teams agree to blacklist a good player with no criminal record? His jersey is still a top seller.

There could be many reasons why Kaepernick can’t find work in the NFL. Some could be quite unsavory. Yet critics argue Kaepernick’s unemployment is strictly due to his playing record. Running a horse race to see which reason is the winning one is impossible without the right data. So I started poking around to see what I could find.

Deadspin recently published an article about NFL contracts, and it made me wonder about what the nature of these contracts might reveal about conditions in the market for NFL players. It turns out there is some evidence that teams coordinate on hiring decisions by coordinating on the contracts they offer players. This coordination could also be responsible for a culture that restricts self-expression.

NFL contracts

Contracts dictate who gets what and when. Looking down from above we can divide the landscape into two levels of contracting: first between the NFL and its teams, and second between teams between players. There is a lot more nuance, of course. For instance, players are actually represented by a collective bargaining agreement (not a union), and there are often conflicts between a team’s front office making acquisition decisions and the coaching staff making retention decisions. This is just to keep things simple.

Start with league-team contracts. TV deals are the league’s main revenue source. The NFL negotiates with broadcasters and then splits the cake equally across the league’s 32 teams (each team earned $226.4M in the 2014 fiscal year). Not only does this cake-cutting make the NFL one of the world’s richest professional sports leagues. It also provides big incentives for teams to toe the company line as they effectively form a coalition managing shared assets in the form of football players.

Deadspin points out that a major difference across U.S. professional sports contracts is guaranteed pay, the amount of a contract to which a player is entitled. One very interesting fact the article reports is that few NFL player contracts are completely guaranteed – even though there is no rule preventing teams from committing sums to players. I wanted to see this for myself. Do NFL contracts look similar in their guarantees? And how do they compare to contracts in other professional sports like basketball that also require no guarantees?

Scraping NFL contract data from the web

I scraped all active player contracts in the NFL from Spotrac, a website with financial data on professional sports. They conveniently list the value of a contract and how much of it is guaranteed. They also list contract length and player details like position. Similar data for the NBA is available, another rich league with a similar two-level contracting structure.

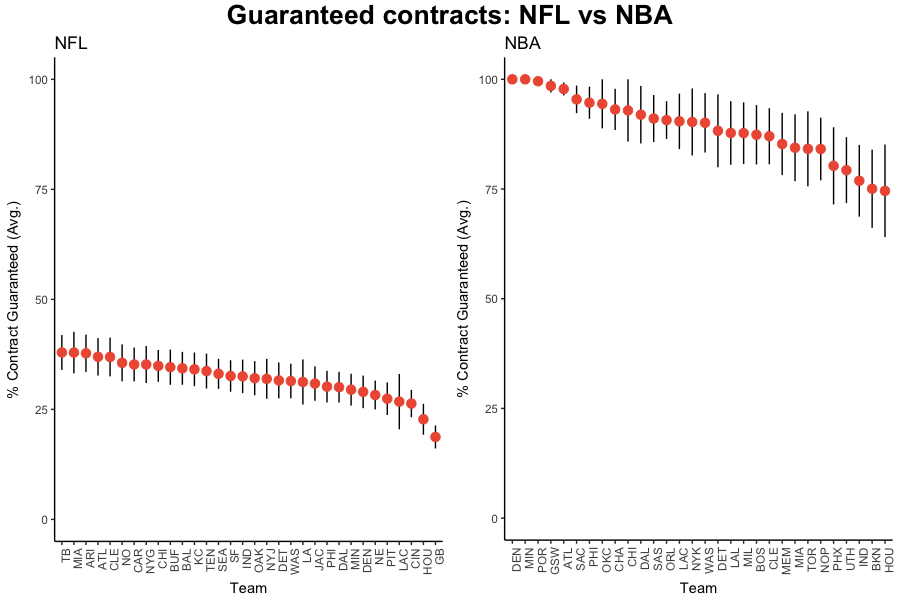

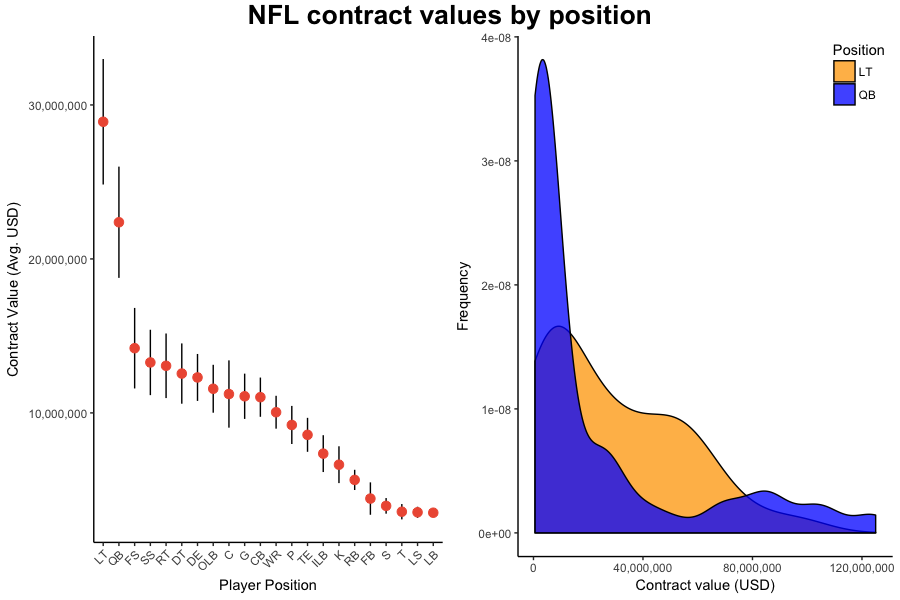

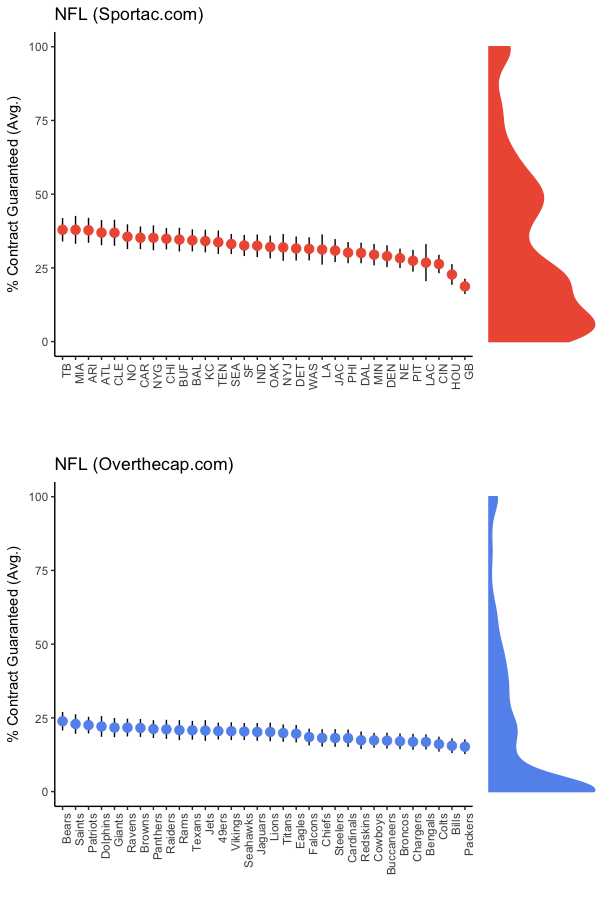

I calculated the mean and variance of guaranteed money to players across teams and plotted the leagues next to each other. If teams are coordinating on contracts then we should expect to see no significant differences in guaranteed pay:

Indeed. Teams in the NFL seem to converge on low guaranteed pay compared to teams in the NBA. Again, what makes this so interesting is the absence of any rule that requires contracts to include a certain amount of guarantees. From the Deadspin article:

“‘Back in the old days, owners could give guarantees; it’s just that they never did,’ Gary R. Roberts, the author of a 1992 Marquette Law Review article titled “Interpreting the NFL Player Contract” and the current president of Bradley University, told me. ‘They didn’t have to. Nobody else was doing it, so there was no leverage the players had to insist on guarantees.’”

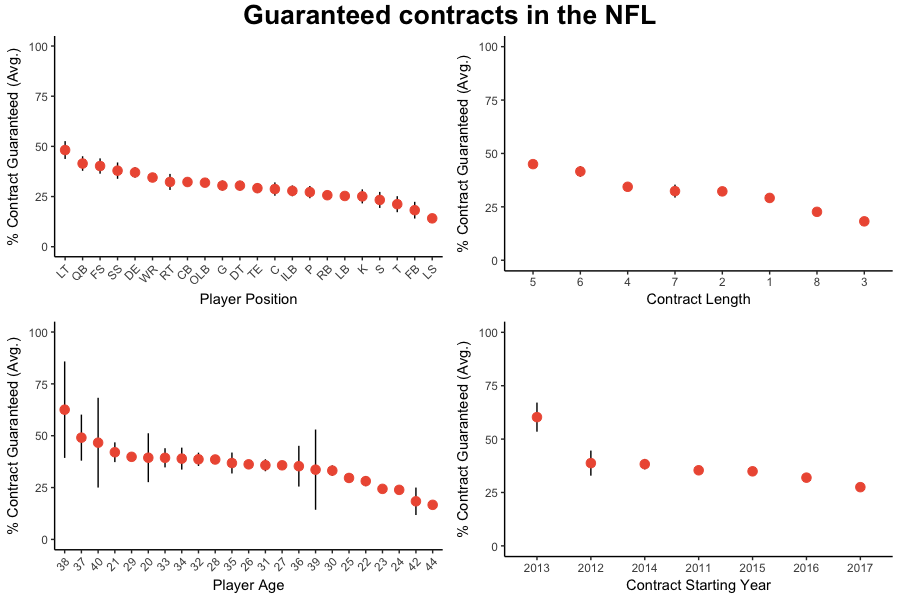

Digging deeper, it is clear that an NFL player cannot get much in the way of guarantees:

There isn’t a clear relationship between contract length or age – though for some reason, 2013 was a good year to sign a contract. Older players have the best shot at guaranteed money, but there is a lot of spread. Players can supplement their income with sponsorships, but sponsorships are a function of player quality and brand, meaning the few famous players are likely to attract the lion’s share of sponsorship wealth. This only increases the value of contract guarantees to everyone else.

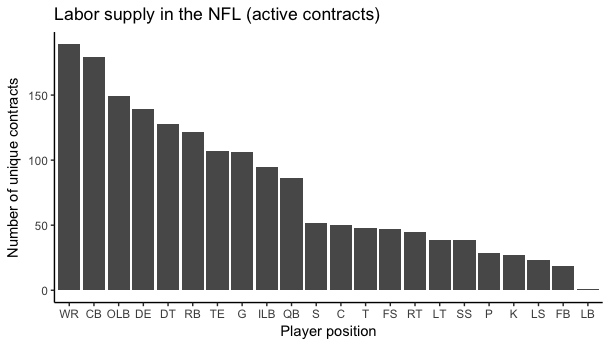

Surprisingly, left tackles get the most guaranteed money. I don’t know enough football to understand why, but as seen below, it seems that left tackles are scarce:

Quarterbacks are scarce, too, but left tackles enjoy more consistency in guarantees:

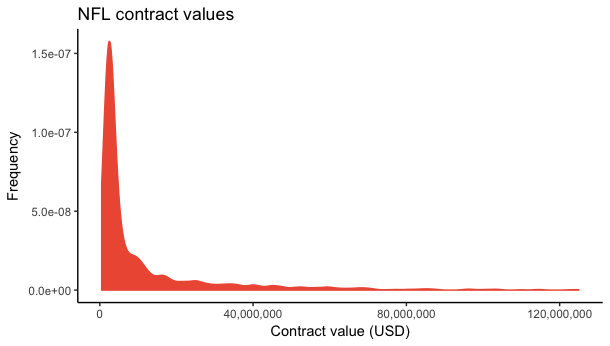

The sort-of power-law in quarterback contracts is pretty consistent with the big picture, view of NFL contracts, a market where a few players are fabulously rich and others just ordinarily so:

There are limitations here, but it seems plausible that business-as-usual in the NFL could be due to coordination between teams, since coordinating on low guaranteed pay is in their collective interest. Later on I address these limitations in more detail. For now, let’s turn to what the absence of guaranteed contracts implies for player incentives, and more broadly, the league’s attitude toward self-expression by players like Kaepernick.

Contract theory

Why does guaranteed money matter? Fans argue that players are nicely compensated. Players certainly won’t starve, even if they only play a year of pro ball.3 But set aside the sums. Look instead at how guarantees affect incentives. It goes back to a fundamental problem firms face when writing contracts with employees.

To fix thoughts, imagine a firm hires you to invent a technology that increases its productivity. The firm hands you a fixed wage and in return you show up to work everyday. This part of the contract is straightforward. But what about the technology? Before it’s built, nobody knows what it will look like and what its value will be.

Think of a football player as an employee who produces two things: wins and brand. Producing wins is simple enough to contract: more wins, more pay. Brand is harder. If the player gets famous, who collects the proceeds of fame? The team could sell more jerseys, but the player could sell his image to sponsors. Or what if the player commits domestic abuse? Who then foots the bill – the forgone losses on brand? All this surplus – the combined value of wins and brand – is unknown on signing day, when a college player joins a team and signs a contract.

Both cases feature a similar problem: there are things the firm would like to contract on but can’t. Contract theory calls this the problem of incomplete contracts. They feature heavily in so-called principle agent problems, where a principle (the team) hires an agent (a player) to produce stuff for it. Principles and agents often have different incentives: the principle wants the agent to maximize its welfare in exchange for wages, but the agent has her own ideas.

There is a workaround: let property rights substitute for performance rewards. “Property rights” basically means ownership. Instead of just contracting a set of rewards contingent on performance, the principle and the agent can negotiate on who owns whatever the agent produces. If the agent has no ownership of the fruits of her labor, she has scant incentive to exert more effort that what her wage covers.

So even partial ownership can encourage her to work harder. This is because ownership increases bargaining power. If the agent sees more value in her production than what the principle pays, she can take it elsewhere. In the end, the firm has to balance sticks and carrots – balancing ownership over the product with motivating the employee to innovate and produce a better product than she would otherwise.

Assuming, of course, all the firms in the market aren’t coordinating in a way that makes it harder for our agent to make good use of her property rights. For example, what if teams in the NFL coordinate to prevent an above-average quarterback with outspoken and unpopular views from getting a job?

Contracts, coordination and culture

Business-as-usual contract design may not have emerged from a deliberate plan, but it seems plausible that owners coordinate to keep it afloat since it is in their collective interest. And if teams coordinate on how they compensate players, it is plausible they could coordinate on hiring decisions.

As they stand, NFL contracts allow teams to pass risk onto players through low guarantees and prevent any one player from amassing a lot of bargaining power. They also support a culture that demands obedience. Maybe it has to do with brand. Teams and the entire league benefit from good branding, but in player-team negotiations, brand is hard to contract on. Cultivating an atmosphere that rewards compliance and punishes deviant behavior – even peaceful protests – is a handy substitute for complete contracting.

How this coordination is or would be executed is unclear. Teams probably won’t make a player sign a contract that asks them to withhold from exercising their first amendment rights. But they might share an understanding of what they believe is right and wrong. And you might expect this understanding to be related to league-team contracts. This could explain why a peaceful protest is more likely to blacklist a player than domestic violence.

Since we don’t observe all NFL contracts in full detail, we are limited to speculation. The only NFL contract I could find belongs to Arian Foster of the Houston Texans (oddly I found it on the SEC website). Section 15 is titled “Integrity of the Game”. It begins:

“Player recognizes the detriment to the League and professional football that would result from impairment of public confidence in the honest and orderly conduct of NFL games or the integrity and good character of NFL players.”

It specifically discuss penalties for accepting bribes and throwing games, but teams might give a wide berth when deciding what constitutes “impairment of public confidence”. This past season we learned that kneeling during the national anthem upsets many fans, more so than instances of domestic violence. But maybe the league and its teams have views of public confidence and the integrity and good character of NFL players that extend beyond what is explicitly set in a contract. Protecting a shared brand is consistent with this line of thought, echoing the concerns of Mr. Biscotti, the Ravens owner.

It might also explain why Kaepernick has little public support from his peers despite enjoying their support privately. Go back to guaranteed pay. When a player is unsure how much of his contract will actually pay out, as most players are, expect him to have a strong incentive to comply with all his team’s formal and informal regulations. There are probably many ways in which strict compliance with the law of the land is baked into football culture. After all, this is a sport where a huge set of players who never actually play in real games are needed to help train the few players that do. Contracts trimmed with some performance-based bonuses but low guarantees are one such way.

Limitations

It could be that this convention on player contracts emerged without any coordination, though that seems unlikely. Michael Vick was hired after he was found guilty of running a dogfighting ring. The Dolphins brought a player out of retirement rather than sign Kaepernick.

Still, there are a few concerns about this work out with the data. Here are just a few.

For starters, sports agents tend to broker deals on behalf of players, but agents and players often have different incentives. According to Deadspin, agents have an incentive to keep contract guarantees low for their clients. It allows them to broker mega-deals that garnish media attention, and hopefully, business from other players. The data from Sportec doesn’t provide a look into this dimension of player contracts.

Another issue is that we don’t observe all the tradeoffs players and teams make when negotiating. NFL players accept contracts with low guarantees despite incurring huge health risks, but according to a recent Harvard study, they receive very good health care, even in retirement.

From the team’s point of view, not only are they evaluating the expected benefits of hiring a player compared to other players. Teams also have to weigh the stream of expected benefits through time. Player injuries make a difficult problem even harder. Risk of injury varies across players, and I’m guessing no team has a grasp on what this distribution looks like. (The same Harvard study claims the likelihood of injury in the NFL is significantly higher than in other U.S. professional sports.) So even if there were no coordination among teams, no single team has an incentive to offer low guarantees. However, the risk of injury is not easier to predict in other sports like basketball, nor does it impose trivial losses on a team, and yet the NBA offers more guaranteed pay.

Finally, the data from Sportec might be incomplete. I don’t know exactly how the data are collected. Maybe there is better data elsewhere. Poking around led me to OvertheCap. Contracts look similar across the two sites, but not identical:

Finally, it is worth pointing out the strange predictions that come out of this data. If guaranteed pay really is an important component to the Kaepernick story, then players with more guaranteed pay should have more bargaining power, meaning left tackles and quarterbacks should be the most outspoken. I don’t know if this shakes out in reality (though Tom Brady has been pretty quiet about all this). An obvious confounder is self-selection: players groomed for these positions may decline to be outspoken.

Conclusion

Kaepernick’s protest was almost too effective. It caught more public attention and drew more score from NFL leadership than players committing domestic abuse and other acts of violence.4 And now Kaepernick cannot find work in the league.

Are NFL teams coordinating against Kaepernick? The claim is gathering steam but it is difficult to evaluate. If true, then it would mean teams have some way to exercise control over labor. One way to control labor is through contracts. If teams can coordinate on the terms that players sign in exchange for their labor, then maybe they can indeed coordinate on hiring decisions. Data scrapped from Sportec.com show that teams offer almost identical average levels of guaranteed pay – despite there being no formal requirement for teams to do so.

There is a lot I don’t know about inner machinations of the NFL. This was just an attempt to get a handle of a strange and frankly sad story. I hope there is more to come. One thing about professional sports is that they are among the few labor markets where some contract data – and even data on labor market inputs – are available. Recent findings about cognitive health in former players means contract design will come into sharper focus. Unless the game changes to become much safer, players may be forced into making a difficult decision: trading-off present benefits in the form of higher contract guarantees with future benefits in the form of better medical care after retirement.

Code

The data and code to reproduce the figures are available on GitHub.

-

An unnamed general manager later confirmed this fear. ↩

-

Bizarrely, the Baltimore Ravens said they consulted former player Ray Lewis in their deliberations on Kaepernick. Lewis was a strange choice. Some years ago, Lewis was caught up in a murder trial and convicted of obstruction of justice. The NFL suspended him just two games the following season. ↩

-

The NFL is known to have an inconsistent record at disciplining players who commit domestic abuse. ↩