Do Something

June 2020

Co-evolving norms in Black Lives Matter and COVID-19.

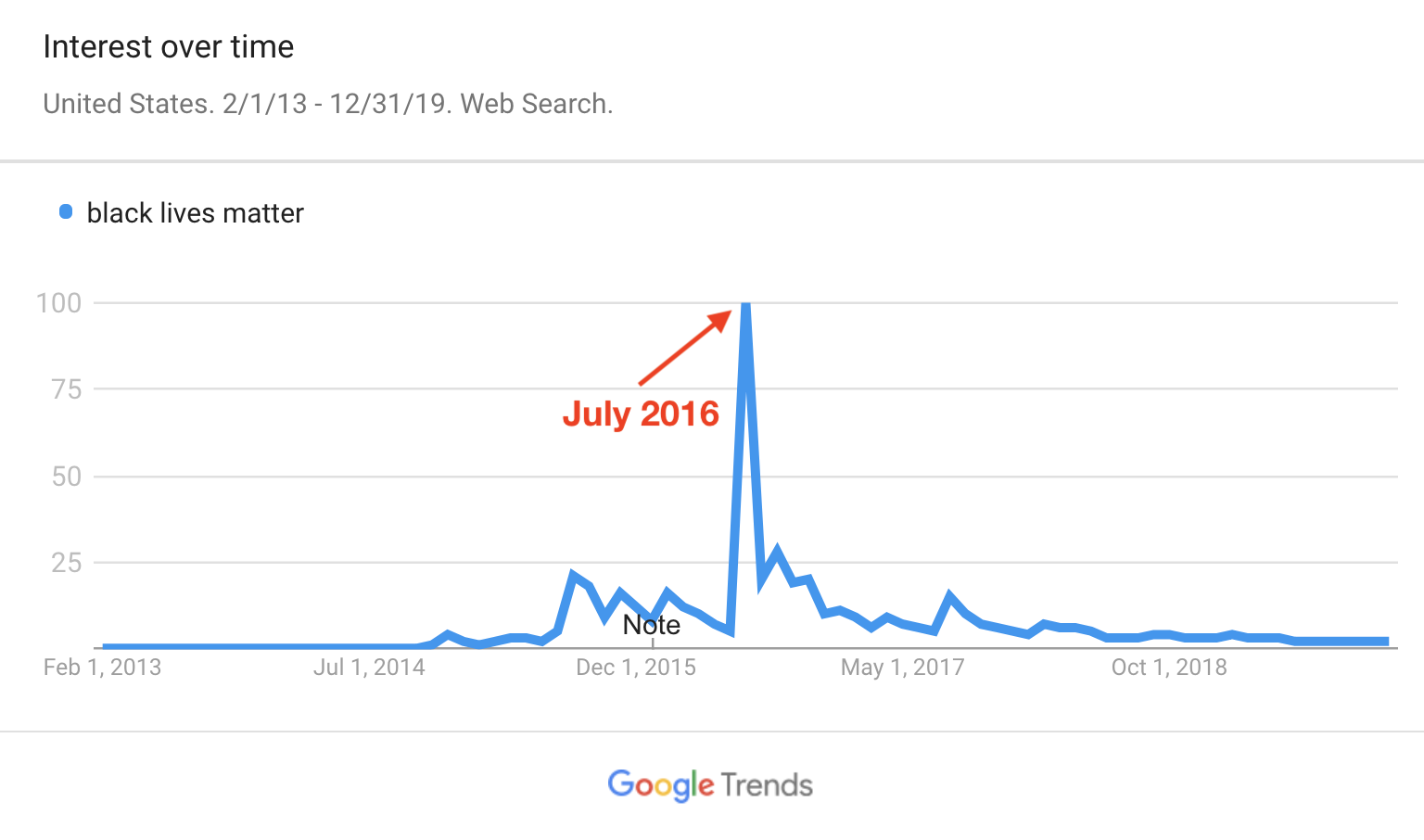

Black Lives Matter (BLM) started in 2013 to protest racial injustice and police brutality. Search interest in the idea flickers over time, like most things:

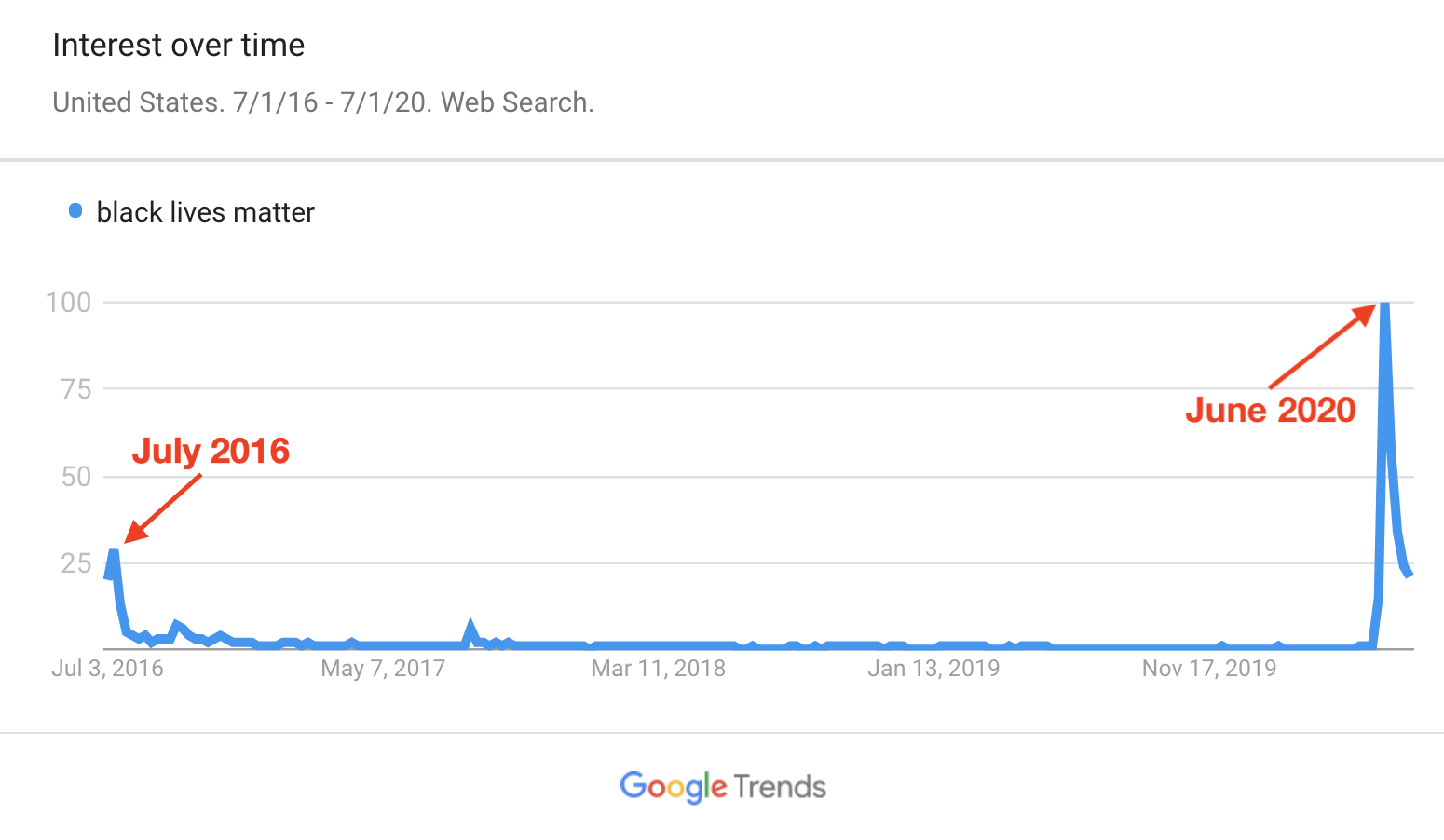

but this June it hit an all-time high following George Floyd’s murder:1

It’s unlikely this spike in Google searches is driven by population changes, internet access or other confounders. This time round just feels different.

You can feel it in the streets. All through June, multi-racial, intergenerational and largely peaceful protests sprouted up in cities large (like Boston, MA) and small (like Bethel, OH) and lasted for weeks. They sent a clear message: “Do Something”. In a Boston protest a few weeks ago one of the most common signs was “Don’t just be not-racist, be anti-racist”. (Searches for “anti-racist” also hit an all-time high.)

Norms coordinate pressure

Public pressure can change unequal societal conventions (Hwang et al. 2017) – like feudalism, or different policing for different races (Fryer 2019).2 But the stop-start nature of BLM underscores the challenge of coordinating anger into action. Norms – guidelines for social behavior – often emerge to solve these kinds of coordination problems. “Do Something” is not just a message, it’s a norm. As in: don’t just sit there, don’t just post on social media, do something!

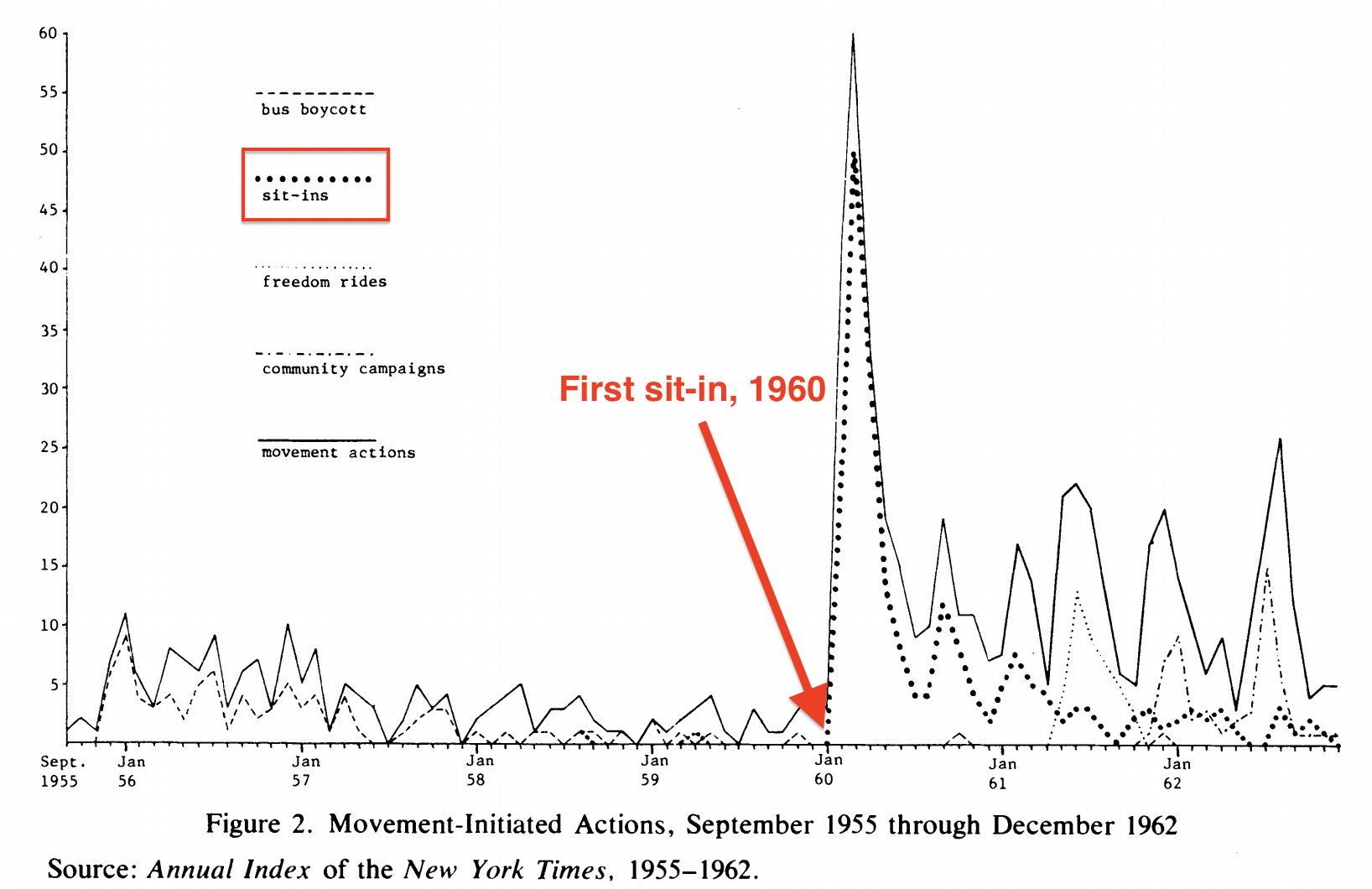

A similar pattern played out in the first Civil Rights movement. Protests against segregation started in the 1950s but didn’t catch on. Then, in 1960, four black college students sat down at a whites-only lunch counter (basically a diner) in Greensboro, NC and tried to order lunch. They were denied. But the revived protest method (the first sit-in was in 1939 at a library in Alexandria, Virginia) immediately took off:

From McAdam (1983), with added annotations.

Compared to other protest methods the sit-in had a few advantages. It only needed a few people, it could be done in big or small towns, and most importantly, it worked: by 1961 over ninety cities in ten states desegregated lunch counters (McAdam 1983).

Sit-ins worked were because they imposed direct costs on segregation (a sit-in often drew violent segregationists mobs that shut down entire towns) and because they challenged the segregationist image of white superiority. McAdam (pg. 744) quotes a telling passage from an editorial in the pro-segregationist newspaper Richmond News Leader in 1960:

Many a Virginian must have felt a tinge of wry regret at the state of things as they are, in reading of Saturday’s “sit-downs” by Negro students in Richmond stores. Here were the colored students, in coats, white shirts, ties, and one of them was reading Goethe and one was taking notes from a biology text. And here on the sidewalk outside, was a gang of white boys come to heckle, a ragtail rabble, slack-jawed, black-jacketed, grinning fit to kill, and some of them, God save the mark, were waving the proud and honored flag of the Southern States in the last war fought by gentlemen. Ehew! It gives one pause.

Sit-ins stopped when segregationists devised counter-tactics (e.g. new trespassing laws). But by then the protests had drawn national attention. The notion spread that times were changing and that people had to do something. Wright (2013) shows that white businessmen promoted blanket desegregation when President Johnson planned to only desegregate interstate retail chains. By the time the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 many businesses in the South had voluntarily desegregated.

That is why this time round with BLM feels different: the norm “Do Something” has re-emerged. People have started donating to bail funds. (Search interest in “bail funds” also peaked in June.) The Minnesota Freedom Fund received $150,000 in donations in 2018 – and $31 million so far in 2020. And of course, people are protesting in huge numbers, stateside and worldwide. The map below (source) shows all protests with at least 100 participants:3

All this action is having an effect. Laws are changing: many states have banned police choke holds.4 Culture is also changing. The NFL did an about-face and will no longer fine players who kneel in protest during the pre-game National Anthem. NASCAR banned Confederate flags. The TV show COPS was finally canceled.

Why now?

George Floyd’s death was videotaped, but so was Philando Castile’s. 2020 is an election year, but so was 2016. Dallas and Charlottesville came and went. Why is “Do Something” re-emerging now?

One glaring difference between this year and every other year of BLM is COVID-19. What role does the pandemic play? Here are two thoughts.

First, the pandemic has forced people to confront things long taken for granted. Small things, like how long to wash your hands (at least 20 seconds) and not touching your face. Then big things – like mass unemployment and the systemic issues that have caused the virus to disproportionately affect black people and ethnic minorities (EPI 2020, CDC 2019).

Second, the pandemic has also forced people to think harder about social interactions, since that is how the virus spreads.

We have new norms like “Wear a Facemask” or “Maintain Social Distance”. But state and municipal enforcement are scarce (or in some cases unwilling), so people have to enforce them. Telling somebody to wear a facemask is awkward at best and hazardous at worse. But norms unravel without people to enforce compliance and spread the word.5 This might be why places with higher social capital have fewer infections (Borgonovi and Andrieu 2020, Bartscher et al. 2020).

This matters because good things tend to come in twos: a norm that promotes prosocial behavior in one setting (like public health) often co-evolves with another norm in another setting (like civil rights), when neither would emerge in isolation (Bowles and Gintis 2011). So it’s possible this sense of “if not us then who?” from COVID-19 has spilled over into other social issues like BLM.

Will it last?

Norms last when they are internalized and passed on. For instance, trust is one of the most important inputs to social life, so kids are taught to internalize the norm “Don’t Lie”. This is probably why most people on average don’t lie (or at least they don’t stretch the truth to the fullest extent), even when they know they can’t get caught (Abeler et al. 2019).

It’s unclear how much “Do Something” (or the general idea of racial equality) was internalized during the Civil Rights movement. Segregationists believed de-segregation was a zero-sum game that would simply redistribute wealth. Turns out it wasn’t: desegregation increased average wages for both black and white workers. Even so, the belief that desegregation made people worse off endured, and this contributed to a decay in the benefits to desegregation over time (Wright 2013).6

Today we also see backlash to ideas that would make everybody better-off. Some people are outraged about wearing facemasks. Calls to reduce police brutality divide opinions. The fact that the US is polarized (even on whether COVID-19 is a problem) does not bode well. Norms don’t spread uniformly (Young and Burke 2001); polarization may keep them from ever reaching some places.

Polarization may also affect whether a norm is internalized in places where the norm spreads. Since polarization amplifies extreme beliefs, it could also increase the payoffs to strategies that promote those beliefs using sticks (like online shaming, which is fast) rather than carrots (like consensus-building, which is slow).

Sticks create incentives to comply with norms; the problem is that people are motivated by more than just cold, hard incentives (Bowles 2008). Fines can extinguish our concerns for the welfare of others (Fehr and Rockenbach 2003). We even see this with kids, who develop these “other-regarding preferences” between ages 3-4 and 7-8 (Fehr et al. 2008). They lie less when adults appeal for honesty; they lie more when adults threaten them with punishment for dishonesty (Talwar et al. 2015).

Silver linings

It’s too early to tell what will happen. The how, why, where and when of norm emergence is an open question (Kimbrough and Vostroknutov 2020). The good news is that norms do emerge and change does happen. That seems obvious, but it’s worth remembering.

For instance, we see change between generations. In 1965 most southern whites approved of laws banning interracial marriage; by 2013 most Americans were in favor of interracial marriage, and the south was about level with the east and the midwest (the west had the highest approval).

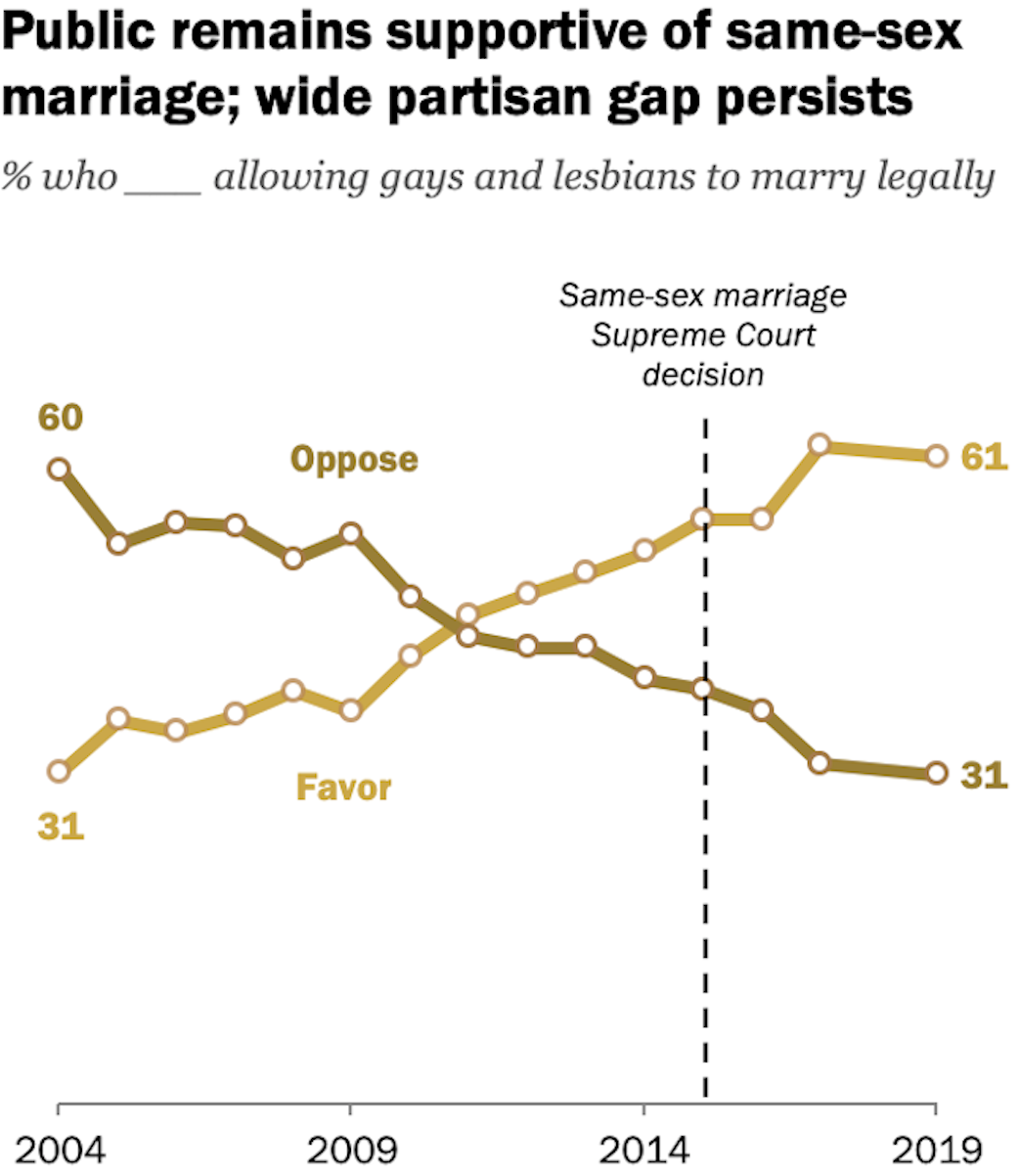

Even better news is that change can happen within generations. For instance, many states didn’t repeal penalities for homosexuality until the early 2000s. Within fifteen years, a majority of Americans supported gay marriage:

-

Ditto searches for “police”, “protest”, “racism”, and more. ↩

-

Fryer finds that black people are subject to significantly more non-lethal police force (like beatings) on average, but there is no significant race effect on lethal force (like shootings), holding all else constant about a police encounter (Table 2 in the paper). Weisburst (2019) corroborates; Hoekstra and Sloan (2020) contradict. This is an ongoing literature; we can’t yet draw sweeping conclusions.

Not that some outlets aren’t trying. For example, Fryer’s paper does not say “there is no racial bias in policing”, even if that is the claim of some newspapers. The paper is descriptive: it simply estimates the probability of lethal and non-lethal force conditional on contact. This does not rule out the possibility that biases play out on the probability of contact.

In general, racial bias (animus) is difficult to measure statistically. But I think the bigger question is whether the debate and ensuing policy interventions need to hinge on population averages. Fryer’s paper also shows that variation within precincts matters a lot: controlling for precinct fixed effects drops the odds of more non-lethal force on a black person relative to white person from about 50% to 18%. Similarly, Hoekstra and Sloan’s estimates appear to be very sensitive to officer fixed effects. In a recent op-ed Fryer writes (in the same newspaper that over-simplified his findings): “Our analysis tells us what happens on average. It isn’t average when a police officer casually kneels on someone’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds.” ↩ -

When the English Premiere League resumed fixtures this month, player names on jerseys were replaced with “Black Lives Matter”. ↩

-

Here is a recent thread on new research on policy interventions to reduce racial bias in policing. ↩

-

Axelrod (1986) shows in an agent-based model that enforcement (e.g. “wear a facemask”)and meta-enforcement (“tell other people to wear a facemask”) sustain norms. Galan and Izquierdo (2005) clarify the long-run effects of Axelrod’s model and showed that while norms can emerge in equilibrium, whether they last depends on factors like the payoffs to enforcement and the penalties to non-compliance. ↩

-

Many businesses didn’t hire black workers, believing them less productive. But Wright points out that productivity in the segregated south was socially determined: black schools were underfunded and thus generated less productive workers. This productivity gap collapsed with desegregation. Similarly, Cook (2014) shows that innovation (in terms of patents filed) was also socially determined, as black inventors were less protected than white inventors. ↩